sun circle:

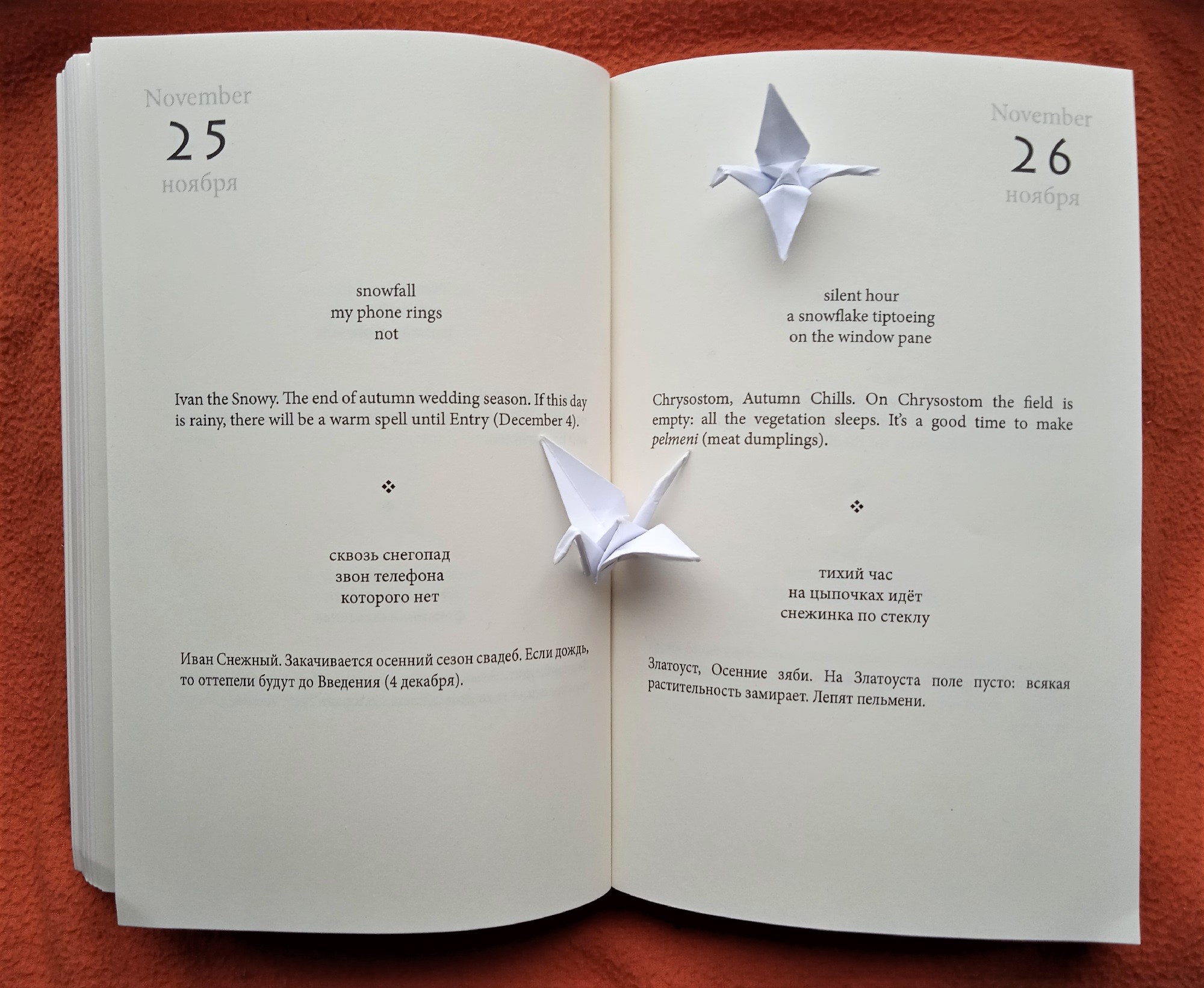

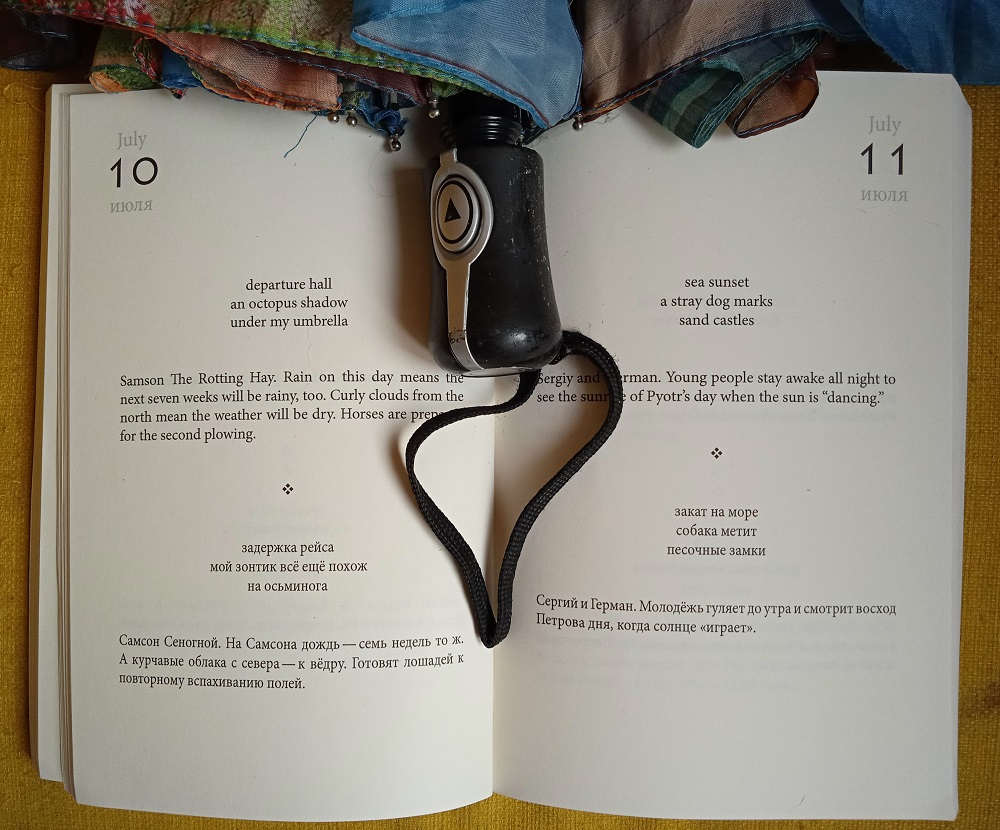

haiku calendar

Free Telegram bot: @haiku_suncircle_botBuy a paper book: Sun Circle. Haiku Calendar

Contact the author: lexa@eva.ru

ABOUT THIS BOOK

"The best way to fully appreciate a saijiki is to build one yourself."

— William J. Higginson, The Haiku Seasons

"The best way to fully appreciate a saijiki is to build one yourself."

— William J. Higginson, The Haiku Seasons

Seasonal organization of poetry books is a well-known tradition in Japanese literature. It’s mostly common for haiku anthologies since one of the key elements of this poetry is a season word (kigo) that connects every haiku to a certain time of year. For example, “frog” indicates spring, while “moon” is usually an autumn word.

However, many kigo come from the deep past, so they don’t provide clear seasonal associations to modern readers. In order to preserve the poetic tradition, special dictionaries of season words — saijiki — were created in Japan: the description of every kigo would come along with samples of haiku that included this kigo. This way a dictionary turns into a poetry anthology.

The author of Sun Circle became acquainted with the principles of saijiki in 1996 when William J. Higginson, a famous researcher of Japanese poetry, invited him to take part in Haiku World, the first international haiku almanac made in the form of a saijiki. This project showed that modern poets used various season words connected to their local traditions, and suggested it would be interesting to see “kigo dictionaries” from different countries. This idea lead to the creation of Sun Circle, a haiku collection based on the Russian folk calendar where many “season words” could be found — not just for every month but for every day of the year.

"The simple folk is better in keeping its primordial way of life." — Vladimir Dal, Sayings of Russian People

As a piece of folklore, a Russian folk calendar cannot be presented in one “official version.” It’s a vast patchwork of weather wisdom and daily life rules connecting nature phenomena, human activities and popular beliefs of different times and regions. Researchers of pre-Christian rites of Eastern Slavs recognize the influence of ancient Greece, Rome and the Middle East. On the other hand, equivalents of the major Slavic festivals dedicated to solstice, equinox and season changes could be found in many pagan calendars of Northern Europe (Yule, Imbolc, Ostara, Beltane, Litha, Lughnasa, Samhain, etc.).

When the Christian Church came to Russia in the 10th century, it brought its own holidays. However, the old folk calendar was tightly connected to the rural economy, family rites and other daily activities — so the Church couldn’t eradicate pagan traditions completely. Some Slavic holidays still retain their ancient names; in other cases, Christian saints got “local residence,” becoming the patrons of local crafts and seasonal rituals. The resulting “Russian Folk Orthodoxy” resembled a similar cultural phenomenon in Japan — a synthesis of Buddhism and Shinto.

Until the 19th century folk calendar wisdom was transferred from generation to generation, primarily in oral form. To memorize it better, people used proverbs and songs where the names of the saints were rhymed with the omens and activities for the corresponding day: “Evsey — ovsy otsey” (“Evsey — sow oats”). So the calendar was a folk poetry collection as well.

Another similarity with Japanese season word dictionaries is the very name of Russian folk calendar — Mesyatseslov ("word of the month"). Also, the names of months in both Japanese and Russian ancient cultures were connected to similar season phenomena. For example, May in both cultures was about flowering ("tsveten" in old Russian, "uzuki" in Japanese), autumn would come with the month of falling leaves ("listopad" in Russia, "haochizuki" in Japan), and December was the month of freezing ("studen" in Russia, "shimotsuki" in Japan). To create calendar entries for Sun Circle, the author used books of folk beliefs, omens and sayings collected in the 19th century: that’s when Vladimir Dal, Alexander Afanasiev, Ivan Snegirev and other Russian ethnographers wrote down the oral presentations of folk calendar in their purest forms.

Sources of later years show that the Revolution dramatically undermined the tradition — both by new ideology and through the Gregorian calendar. The 13-day shift of all dates led to a mix-up of holidays in modern reconstructions of the folk calendar — their omens often don’t correspond the seasons. To fix these discrepancies, the author of Sun Circle compared different versions of folk calendars with the calendars of natural phenomena and agricultural activities in Central Russia.

Nevertheless, it should be understood that the calendar presented in this book is a very simplified version of the Russian folk calendar. The goal of this work was only the detection of the most popular sayings and signs of weather wisdom for each day, with short descriptions of these “season words” so they could be used to organize the author’s haiku in a saijiki-like collection. Real traditions of Russian folk culture are much more complex and diverse. Those interested in them should consult more serious ethnographic studies.

"I was impressed especially by the haiku written by Alexey Andreyev in Russia." — Kazuo Sato, judge for the Mainichi Haiku Contest 1997

Alexey Andreev was born in 1971 in Novgorod. He graduated from Leningrad State University as a mathematician, but he’s mostly known as a writer, journalist, creator of the first Russian haiku e-zine Lyagushatnik (Haiku.ru) and winner of top prizes in many international haiku contests, including the Shiki Haiku Contest (1995), Mainichi Haiku Contest (1997 and 2017), Japan-Russia Haiku Contest (2013), Kusamakura Haiku Competition (2015), European Quarterly Kukai (2017), NHK Haiku Masters (2017), and HIA Haiku Contest (2018).

In addition to contest-winning poems, this book contains the best haiku the author has published in international anthologies (Haiku World, Haiku sans frontieres, Red Moon, Butterfly Dream) and haiku journals world-wide (Frogpond, Woodnotes, Presence, Heron’s Nest, Acorn, Modern Haiku, Chrysanthemum, Bones, Akitsu, World Haiku Review, A Hundred Gourds, Asahi Haikuist Network, DailyHaiku, Under the Basho, and others). A few poems were published earlier in Alexey's first haiku book Moyayama. Russian Haiku Diary (ASGP, Chicago, 1996).

Translations were made by the author himself. Many are not literal translations but rather adapted versions. Likewise, the correspondence between haiku and calendar entries shouldn’t be taken literally, since the calendar is ancient while the poems are modern and based on the author’s personal experience. For instance, the author doesn’t ride horses in his daily life, so when the folk calendar says it’s a horseman’s day, you may see a haiku about a trolleybus driver.

Free Telegram bot: @haiku_suncircle_bot

Buy a paper book: Sun Circle. Haiku Calendar

Contact the author: lexa@eva.ru